I am so blessed to help lead OCD Twin Cities with Alison Dotson, a strong OCD awareness advocate and the author of Being Me with OCD, written for young people struggling with the disorder. Alison is brilliant, fun, a great friend, and a total sweetheart. She and I have been wanting to do something collaborative for a while now, and I’m so excited to be hosting her on my blog today.

I am so blessed to help lead OCD Twin Cities with Alison Dotson, a strong OCD awareness advocate and the author of Being Me with OCD, written for young people struggling with the disorder. Alison is brilliant, fun, a great friend, and a total sweetheart. She and I have been wanting to do something collaborative for a while now, and I’m so excited to be hosting her on my blog today.

Alison and I have both dealt with religious scrupulosity. While many of our struggles were the same (and in some places our stories quite similar), our roads eventually diverged. While Alison gave up her Christian faith and is now an agnostic, my faith has grown stronger.

Today, Alison and I will each answer several questions about OCD and faith– I hope that it will give readers a balanced view.

Did you grow up in a faith-based home and/or community?

Alison: Yes, I was raised Lutheran. We went to an Evangelical Lutheran Church of America (ELCA) church. “Evangelical” in the name throws me off a bit because we really weren’t about evangelizing. My pastors always stressed the idea of God’s grace, and I don’t remember even one sermon about sharing the “good news” with others; at least it wasn’t ever pushed in any organized way.

My family went to church every Sunday, without fail. I wasn’t allowed to stay overnight at friends’ houses on Saturday nights, or have friends stay at our house, because we had to get up for church in the morning. I went to Sunday School. I went to Wednesday School, which is a program we’d get out of school early for and meet at church. I went through First Communion, and as an eighth and ninth grader I went through Confirmation. I belonged to youth groups and sometimes attended a Bible study. One of my cousins was very devoted to her religion; as a Jehovah’s Witness she attended “meeting,” or church, three times a week. All of her friends were from her congregation, not her school. I thought that seemed really cool and I wanted to become more involved in my religious community, too.

At one point I decided I should read the Bible front to back, and I set a goal, something like 10 pages a night. One night I fell behind on my goal, which meant the next night I needed to do more than usual to catch up. I became overwhelmed, which in hindsight seems a little like an OCD symptom, and just stopped somewhere in Exodus.

I became very devoted to my faith and strived to be the best Christian I could be. I really wanted to be perfect and follow the Bible to a T, even though there are contradictions within the Bible that make that impossible! But I was very careful to follow the Ten Commandments. I think the hardest commandment for me to follow as a teenager was honoring my father and mother.

I didn’t just follow the Bible’s teachings; I subscribed to materials for young people, like weekly devotionals. My mom actually thought those reading materials were too conservative and expected too much of me. There was a lot of focus on remaining sexually pure, and the expectation that even my thoughts should be chaste was hard for me to deal with. I began to feel like I had to ask for forgiveness a lot, simply because of my normal teenage thoughts.

Jackie: Yes, I grew up in a Christian home, attended church each week. My parents were very clear that what they wanted most out of life was for their kids to love Jesus. All growing up, Christianity was a very strong theme throughout my life. I could clearly see how much God mattered to my parents, and I think the importance placed on faith is what triggered my OCD to react in themes regarding it (religious scrupulosity). Like Alison, I remember my upbringing advocating strongly for purity as well as good behavior (obedience to parents, not swearing, not lying, etc.), but also for really, truly loving God and knowing him personally. I’ll explain my obsessions in the next question, but I went through a lot of turmoil before my faith became my own at age 14.

Tell us about the onset of your OCD.

Alison: Gosh, when did it start? When I was diagnosed at age 26 I started to retrace my steps, if you will. I remember having what seemed to be OCD symptoms when I was as young as seven years old. As a child I mostly obsessed about my own health and safety. I feared I had cancer, or would be caught in a fire but survive with horrific burns. In middle school I had HOCD, which was particularly hard because I thought being gay was a sin. And I didn’t think I’d be redeemed by simply not acting on the obsessions; I thought God must be really upset with me for even doubting my sexuality. It was torture, complete torture. I figured no one else my age was going through something like that. It affected everything. I had to stop reading, which I loved, and watching TV was hard. I didn’t want to spend time with friends, because what if I had a “bad” thought about them?

This continued off and on in high school, along with other somewhat related obsessions. Many of my obsessions had to do with my body; I didn’t know how young women were “supposed” to look and I feared I might be distorted. I’d look at pictures of myself with my friends and pick them apart, thinking my friends looked so perfect and normal.

Jackie: My obsessions started when I was about seven years old– and they were centered around two of the big no-nos: lying and profanity. I would think of curse words in my head and feel so guilty that I’d have to go confess. I was also terrified of lying, so much so that I wouldn’t give answers to questions of preference, just in case my answer would later change. I thought that would have been the same as lying, and I knew that was bad and sinful. Everything centered around the idea of avoiding sin.

When I was a little older (5th grade), I wondered how I could love a God I couldn’t physically see. I figured this was sinful– to not love God– and I was very ashamed of these thoughts and so I needlessly suffered alone for three years. They were hard years, during a time of life that should not have been hard. I was so ashamed and tormented by this doubt that maybe I didn’t love God that I didn’t tell anyone about my doubts. I cried almost every single day for three years. Finally, when the shame and fear were too much for me to handle, I talked to my mom about it, and she was able to “reason things out” with me. I remember being so overjoyed and lighthearted after that conversation. I loved God. I became a Christian then at age 14 and was baptized at my church.

Soon after that, in 9th grade, I had the thought that maybe God wasn’t real, and again, this was accompanied by a lot of fear. Deep down, I really did believe God was real– and so if I was acting like I didn’t think he was, I was afraid I’d go to hell. It’s hard to explain the next 3-4 years of my life because I think most people entertain those thoughts. But for me, it was like a constant fear, a continual sadness, an obsessive dog-chasing-its-tail sort of rumination that was exhausting.

Later, in college, I worried about the unforgivable sin– worried that I had committed it and would be eternally locked out of heaven. By this point, I loved God and believed he was real, and so it was torture to feel so separated from him. This obsession was my OCD’s crowning glory and plagued me all the way up until I got effective treatment for my OCD.

How did your OCD interact or interfere with your faith?

Alison: Later in high school, probably in my senior year, I started to doubt my faith. I have a very distinct memory of standing in the shower and thinking about people in remote African villages who had never heard of Jesus. I wondered if they were destined for hell just because they weren’t born somewhere like America, and I started to cry. It seemed very unfair, and I really hated the idea. But it was the doubt that had entered my mind that took the biggest toll: I had been led to believe that the only way to heaven was through Jesus Christ, and if you didn’t believe in him and accept him, you would go to hell. Now, there are several things I could say about this (surely there’s an exception for someone in Africa who’s never even heard of Jesus), but at the time it hit me like a ton of bricks that I had just questioned God. I had just doubted my belief.

From there life became torture again, like it had been when I was really struggling with HOCD. This time, though, it was worse. This time the consequences could be far more dire: I could go to hell for my thoughts. I’d heard somewhere that the only unforgivable sin was rejecting the Holy Spirit. So of course that’s all I could think about, day and night. I tried to ward off any blasphemous thoughts, and anyone with OCD knows that’s the exact opposite of what we should do! Anytime a doubt crept in, I prayed for forgiveness. I didn’t want to go to hell. An eternity of torture because I couldn’t stop thoughts I didn’t want there in the first place.

I went to a private Lutheran college. We were required to take a class on Christianity, Judaism, and Islam. One of my classmates was an atheist who openly questioned everything the professor talked about. She voiced my doubts, and I despised her. I attached my tiny baptism cross to a bracelet, and during class I’d rub my thumb over it, pinching it when this classmate spoke up. I felt that I needed it to get me through life; I wanted a constant reminder of Jesus.

Then one day the cross fell off. It could have happened anywhere on campus; I didn’t know where to begin looking. And this was tiny, made for an infant. It was lost, gone forever. What a sign.

I threw myself into my faith, deciding I would just believe everything the Bible said, even the contradictory stuff. I couldn’t cherry-pick what I wanted to believe just because it sounded nice. I read passages in which Jesus said he was the way, the truth, the light. The only way to God was through him. And I hated that because I had begun to have so many doubts about who Jesus really was, and one of my best friends was agnostic.

I wanted to die, but I was afraid of where I’d end up. I imagined leaving civilization, moving to an island or a mountain, where I could be alone with God. I know now that would have driven me mad. One day I went to the new version of Psycho with a friend, and all I could think about was how the man and woman at the beginning of the movie were going to hell because they’d had premarital sex and clearly didn’t think it was wrong.

There were moments of clarity, moments when I felt God’s grace and thought everything would be okay. I cried a lot, and prayed—a lot. I would go to church with friends only to have an unending stream of doubts and fears play through my head. I continued to go to church on Sundays and communion on campus on Wednesday nights, but I no longer believed what I was hearing there, as much as I wanted to, as much as I wanted to go back to a childlike faith. All through college I struggled, desperately grasping at threads of faith and denouncing every doubt. I wouldn’t let myself question God, even though it’s normal to do so!

After four years of religious obsessions, I was exhausted. I’d held on for so long, and tried so hard. In the end I had nothing left, no shred of faith. When I graduated and moved away I decided I was done with religion. I would never go to church again, and there were no Christian classmates around to question it. I didn’t tell friends or family members what was going on; I simply refused invitations to church. I felt a huge relief when I made that decision, like I could finally breathe again. At the time I didn’t realize I had OCD, and I didn’t know I wasn’t doing myself any favors by avoiding my fears. I may have sworn off church, but there would be more obsessions to come.

Jackie: All I wanted was Jesus– and I “knew” that I could not have him because of my sinful, obsessive thoughts. To be clear, the more I grew to love Jesus Christ, the more I feared hell just because it was a separation from him— not because, well, it was hell. Everything in my life had become centered around the person of Jesus Christ, and I was desperate to be accepted by him. So many of my friends and family members reassured me over and over again that I was saved, that God loved me, but I could not believe it. I became very, very depressed and at times even wanted to die– except that, of course, I was worried that that would mean hell for me.

How did you treat your OCD and did that have an impact on your faith?

Alison: I saw a psychiatrist who diagnosed me. I take medication, and in the beginning I read everything I could get my hands on so I felt less alone in my journey. My treatment didn’t have an impact on my faith because by the time I was diagnosed I hadn’t been to church for five years or so, and I had grown comfortable in being agnostic, at least privately. I didn’t tell anyone, really, except people who’d never known me as a religious person.

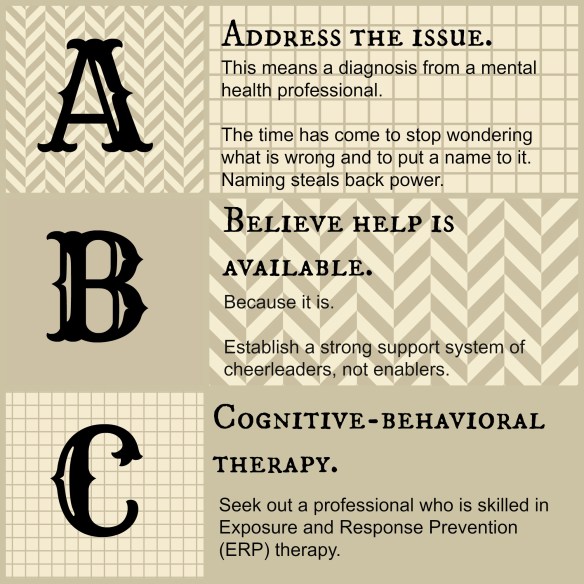

Jackie: I finally was put on the proper medication but even more importantly I underwent exposure and response prevention (ERP) therapy. I was terrified of ERP and what it was asking me to do. I felt confident that if I wasn’t already hell-bound that ERP would seal the deal. I had great friends and family who helped me through those 12 weeks, and there was a part of me that sort of knew that ERP was my last hope, so I pushed through– and found freedom on the other side.

Walk us through changes in your spiritual journey, including where you’re at currently (in regard to faith). Were these changes connected to your OCD?

Alison: I’m happily agnostic. I actually don’t know if I would have ended up here even if I didn’t have OCD, but OCD did speed up the process. If I didn’t have the type of brain that makes me overreact to doubt, I may still be Christian. But I simply could not handle my own questions, and every doubt spurred another and another. I think I had very common doubts about Christianity, but OCD magnified them. They’re pretty reasonable, and if I had had them in a different state of mind I might still have ended up agnostic eventually. But I also had obsessions I still can’t talk about, involving Jesus. I was so inundated with ungodly thoughts I didn’t think I could ever get back to where I had been. The possible repercussions of having such thoughts (i.e., hell) terrified me so much I couldn’t handle thinking about religion anymore. Even though I know OCD is to blame for what happened to me, I can’t help but feel resentful toward religious leaders as well. Being told that even thoughts are sinful was one of the worst things that ever happened to me, because I have OCD. I was a very obedient child, and I still do follow rules and strive to treat people as I’d like to be treated. None of that mattered, though, because my thoughts were so terrible. They made everything feel so pointless; I was doomed because of them, and I couldn’t stop them. Just a terrible cycle.

Jackie: I’m a Christian and I love Jesus Christ more and more every single day. I absolutely abhor OCD, but one thing it did was make my priorities painfully clear to me: Jesus, Jesus, Jesus. Now that the chains of OCD are broken, I can actually focus on Christ and on my faith, instead of on fear and anxiety connected to my faith. I have an incredible freedom in Christ and am so grateful for the way that he never gave up on me.

Anything else you’d like to add in regard to faith and OCD?

Alison: I couldn’t have overcome OCD if I hadn’t been able to embrace doubt. At the time, when I decided to simply stop thinking about religion and to stop attending church, I didn’t know I had OCD and wasn’t treating it properly. But now I know that OCD is a disorder of doubt and that I can’t get through my days without saying, “I can’t control what will happen, and worry changes nothing.” I had to embrace the idea that I can’t possibly know what God really wants. I will never know, in this lifetime, what happens after we die, if Jesus really rose from the dead, if there is any “right” religion. I’ve made peace with those doubts right along with all the others; I had to in order to live my life relatively obsession-free.

Jackie: I agree with what Alison said: I had to embrace doubt in order to defeat my OCD. I had to say to myself, “Maybe God isn’t real” or “Maybe you actually will go to hell,” and in those acknowledgements came freedom. I know it sounds backward. I would have never believed that it could work except that it does, and ERP has opened OCD prison doors for people left and right. Even today, I am comfortable with saying, “I don’t know everything regarding my faith, and that’s okay.” I don’t have to know everything with 100% certainty. That’s where faith comes in!

For more about OCD and religious scrupulosity, go to jackieleasommers.com/OCD

Image credit: Joe Wolf