Hopefully this scene from my novel will give you a better understanding of how OCD works; in it, Neely is attempting to explain OCD to her new friend Gabe. (By the way, Gabe is just finishing up his chemotherapy– hence the lack of hair.) Ask your questions in the comments!! (I would seriously love it if every person who reads this blog asked one question!)

“So, how is Tatum’s Pizza Arcade the best place to tell me about OCD?” he asked while grease from the pizza collected at the corner of his mouth. He wiped it away. “I’m … rather curious.”

I’d been planning this for the last week. “Okay,” I said, “so you get to learn about OCD in three parts tonight. First, I’m going to tell you about it. The second and third parts are more experiential.”

“I’m ready to learn.”

“Obsessive-compulsive disorder is basically where you have these intrusive thoughts—they come out of nowhere and assault you—and then to combat them, you perform some kind of compulsion. Compulsions are more obvious than obsessions—washing your hands til they bleed, checking the oven or the lock on the door over and over and over, being a pack-rat to the furthest extremes, doing weird little rituals.”

“You don’t do any of those things.”

“No. Well, kind of. I have my own rituals. Mine are hard to see because I’m a pure obsessional.”

“So you don’t have compulsions?” I loved the thoughtful way he chewed his food, the earnest look in those pale blue eyes.

“No, I do, I do. They’re just, well, trickier to catch. They’re mostly in my head or to myself. Or well masked.”

“I don’t get it,” he said. “We’re not off to a good start. And this pizza sucks worse than I remember.”

“Let me start over. Okay, so an obsessive-compulsive has an intrusive thought—could be anything—maybe ‘I am going to get sick and die.’ So they hate that this thought keeps hounding them, making them feel sick—so they do something about it.”

“Wash their hands,” he supplied.

“Right,” I said. “You’re getting it.”

“So what about someone who touches the doorknob forty times or something?”

“Same thing. There’s some intrusive thought—and they’ll perform the ritual to temporarily alleviate the sick feelings from the bad thought.”

“Okay, so how about you?”

“My intrusive thoughts are blasphemous.”

Gabe raised an eyebrow—or what was left of one. “Liar.”

“They are,” I insisted. “I think bad thoughts toward the Holy Spirit, and since I’m scared that doing that is unforgivable and that I’m going to hell if I think those things, my head automatically wants to combat those intrusive thoughts. So I say a prayer, the same one over and over to bat down those thoughts.”

He frowned. “And there’s no way to just stop them?”

“Gabe,” I said, borrowing from my old friends Jewett and Nash, “do me a favor and don’t think about a red unicorn. What are you thinking about?”

The corners of his mouth turned up, just slightly. “A red unicorn,” he admitted.

“Well, stop it,” I said. “Quit thinking of the red unicorn. Stop now. Do not think about that red unicorn. Stop—”

“Okay, I get it.”

“So … yeah,” I summed up.

“It’s like warfare up there?” he asked. I nodded.

After dinner, I said, “I want to show you something. Come with me. Bring the tokens.”

We walked to the kiddie arcade. I looked around. “What are we looking for?” asked Gabe.

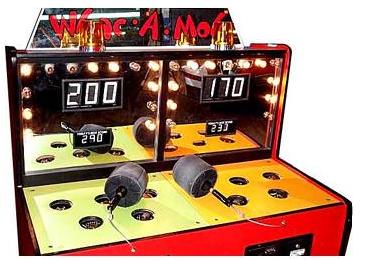

“There it is!” I pointed to an arcade machine that came up to my hips, with five small holes in the top. I took Gabe’s hand and pulled him along behind me toward the machine then maneuvered Gabe into place in front of the game.

“Whac-a-Mole?” he asked, doubtful.

“Whac-a-Mole,” I said, inserting a token into the machine. “Let’s see you go, Reed.” I slapped him on the back for luck.

He made a big show of it, shaking out his shoulders, squaring his jaw, performing minor stretches. I laughed when the plastic moles covered in weathered paint began to pop up randomly from the five holes. Gabe jumped into action, reached for the foam-covered mallet and began to attack the moles, forcing them back into their respective holes as they showed their faces.

Gabe was pretty good—at least, at first. The game began slowly, with moles creeping leisurely out of their holes. But in a short time, several moles began to pop up at each time, and Gabe struggled to keep up. Before long, the moles were out of control, popping up for only a split-second. Gabe let out a choked, surprised laugh as the game sped up even faster. He was wielding the mallet like a boy swiping at the air with a toy sword.

As the machine lit up and the moles retreated, I laughed at Gabe, who looked legitimately surprised to be getting his butt kicked by five plastic mammals. Three red tickets popped out of the dispenser attached to the arcade machine. “What’re those for?” he asked, mallet still in his hand, limp at his side.

“The better you are, the more tickets you get. Then you trade them in for prizes.”

His jaw dropped. I threw my head back and laughed. “Three measly tickets?” he said. “Put in another token.” He wound up with the mallet as if it were a baseball bat.

Gabe played a few more games, getting better and better, the red tickets spewing out of the machine like an overgrown tongue. Still the machine overwhelmed him by the end of every round.

He was no idiot. “So, this is some sort of metaphor for OCD?” he deduced. “The experiential part of tonight?”

I smiled. “You got it. Blasphemous thought—mole rising. Say my prayer—bash it down. Blasphemous thought—mole rising. Say my prayer—bash it down. Now, Mr. Reed,” I said, lowering my voice, “this time, pretend it’s salvation on the line. If you mess this game up—misstep somewhere—you go to hell. Hell being where you are forever separated from the person you love the most.” I dropped another token into the machine; in the middle of the cries of kids and beeps and clangs of arcade games, I could swear that I heard that token hit its fellows in the collection bin beneath the token slot.

Gabe frowned but played his hardest. In the end, when the game had once again gone out of control, it ended. Another string of tickets whirred out of the dispenser, but Gabe only looked at me, and even when I smiled at him, his blue eyes were sad. “I’m sorry,” he said.